In this article, we provide an overview of some of the major advancements in portfolio theory that allow us to address this and various other challenges to the original Modern Portfolio Theory. We believe that these advancements are crucial to successful portfolio construction and are an essential part of our scenario approach. Simply using the original approach could lead to investment decisions that have unintended outcomes, for instance when diversification benefits erode during a crisis. Any investor involved in portfolio construction should therefore be aware of these challenges and how to address them.

The power of diversification benefits and the risk of over-reliance

The principle of diversification as set out in this folk wisdom is applied at an amazing scale today. It is fundamental in Harry Markowitz’ well-known Modern Portfolio Theory, which was developed in 1952 and resulted in a Nobel prize for Economics in 1990. Although the diversification principle is powerful and allows us to construct improved investment portfolios, during the financial crisis diversification benefits eroded as correlations moved towards one. This erosion of diversification benefits poses a challenge to the original Markowitz approach.

The original Markowitz approach in a nutshell

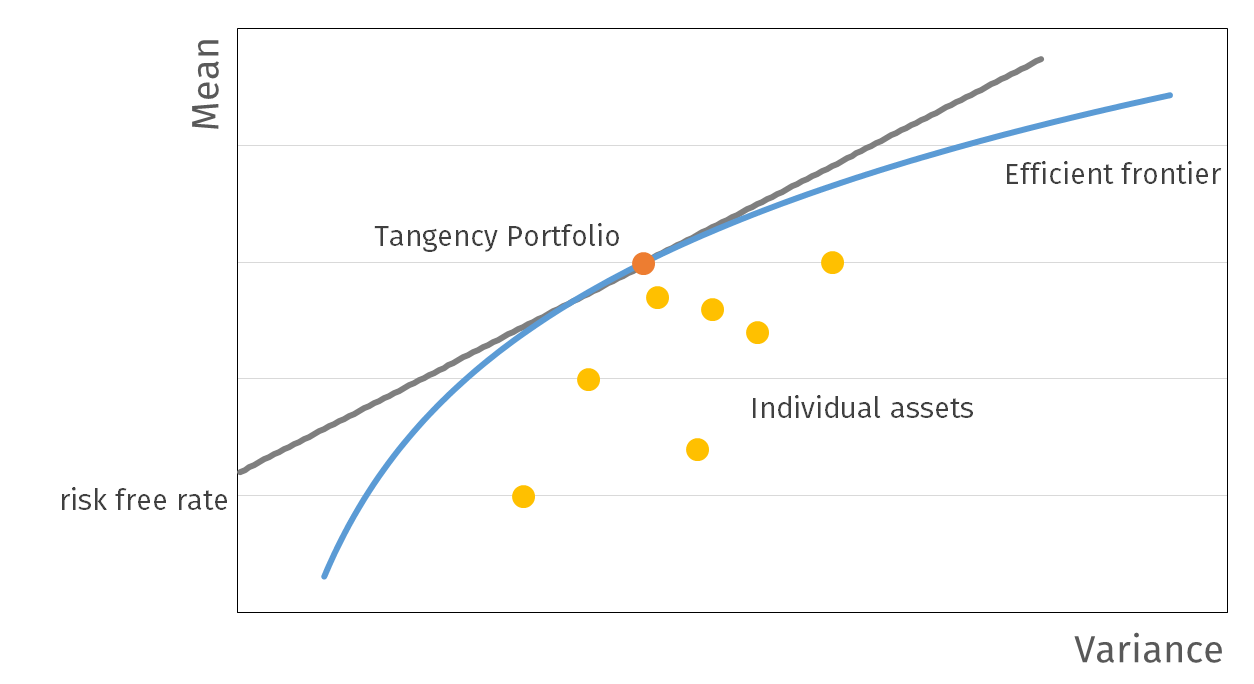

The Modern Portfolio Theory starts from the principle that investors should maximize the expected return of any investment portfolio given a level of risk that they find acceptable. The optimal investment portfolio then diversifies the investment across different assets, taking into account the correlation structure. By tracing out the line of portfolios with the highest return for each level of risk, we obtain the efficient frontier of optimal risk-return outcomes.

The portfolio that provides the highest return per unit of risk is called the tangency portfolio and it is found by drawing a tangency line in the risk-return plane between the risk-free rate and the efficient frontier. The interpretation of this line, which is called the Capital Market Line, is that we may get the best risk-return trade-off by investing in the tangency portfolio and then choose the desired amount of risk by combining with a long or short position in the risk-free investment.

Key research to making improved portfolio investment decisions

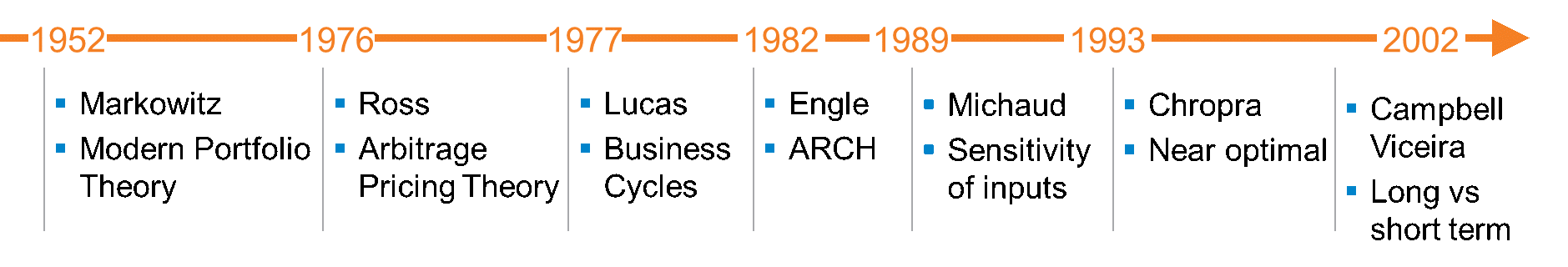

In addition to the erosion of diversification benefits during the financial crisis, various other challenges to Markowitz’ approach have been found since its development. The related research, which has suggested a number of ways to address such challenges, has further refined our knowledge on investing and enhanced best practices. To show how the knowledge has evolved over the years, we show a timeline which gives an overview of a number of major milestones that we would like to highlight.

This list is of course by no means complete, yet we do feel that it provides an overview of key advancements in portfolio theory that practitioners should be aware of. In this article we briefly highlight the importance of each of the pieces and we will publish a range of articles in the upcoming months to highlight each one in more detail.

Ross, Arbitrage Pricing Theory

The arbitrage pricing theory by Ross introduced the notion that returns can be explained based on multiple factors, which are defined as sources of common variation in expected returns. Perhaps the most well-known factor is the market factor, which follows from Modern Portfolio Theory under certain additional assumptions (the Capital Asset Pricing Model). The recent rise of smart beta and factor tracking products is driven by the insights obtained from this theory. Although the factor structure in returns is widely accepted, only a few asset owners apply this concept in constructing their entire portfolio.

Lucas, Business Cycles

Lucas described patterns in how economic activity fluctuates and that there is a certain co-movement among investment called. The business cycles described by Lucas lead naturally to the questions whether the current business cycle state can be identified (e.g. the OECD composite leading indicator) and whether this should influence the portfolio strategy. Informed portfolio construction should take into account how expected returns vary over the business cycle.

Engle, ARCH

Engle already noted in 1982 that the return volatility itself may explain future returns. In light of this research, many investors follow the famous VIX index, which measures the option-implied volatility of the S&P500. The research by Engle gives us key insights in the diminishing benefits of diversification during stress events.

Michaud and Chopra, Fallacy of optimization techniques

Portfolio optimization techniques, while powerful, are dependent on various inputs and should therefore be used with care. Michaud summarized a drawback of efficient frontier optimizations as follows: “the level of mathematical sophistication of the optimization algorithm is far greater than the level of information in the input forecasts.” In work by Chopra, we see that there may be attractive portfolios that were close to, but not on the efficient frontier and hence discarded. Robust optimization may consider these alternative portfolios. Nowadays we see more careful and informed use of portfolio optimizers, a crucial improvement in our view.

Campbell and Viceira, Long Term versus Short Term

In their 2002 famous article, Campbell and Viceira argue that the risk-return trade-off for a long-term investor is inherently different from the risk-return trade-off for a short-term investor. One should therefore explicitly take into account the investment horizon. This insight applies to all types of investors, ranging from Defined Benefit funds to individual Defined Contribution capital management.

Applying the lessons learned

Many advances have been made since Harry Markowitz published his paper in 1952, and there is no doubt that there is still much more to learn. When constructing investment portfolios in practice, it is crucial that we understand and apply all these lessons. Unfortunately, these lessons learned are not yet comprehensively applied in the daily management of portfolios. This means that there is much room for further improvement.

To provide examples of how these lessons can be applied, we would like to highlight some of the stylized facts that we incorporate in our realistic forward-looking scenarios. To start with a well-known stylized fact, our stochastic scenarios allow for time-varying volatility, taking into account the lesson of Engle that benefits of diversification may diminish during stress events. Additionally, and in line with the insight of Campbell and Viceira, our stochastic scenarios provide a term structure of risk and return. The term structure of risk and return for instance allows for the realistic feature that the correlation between inflation and equity returns is higher on longer horizons. Moreover, our stochastic scenarios explicitly describe the business cycle behavior outlined by Lucas. We apply the lessons learned to portfolio construction itself as well through our robust near-optimal portfolio construction approach, which incorporates the lesson of Michaud and Chopra.

At Ortec Finance we aim to improve financial decision making and we aim to incorporate the lessons learned in all our solutions, for both institutional and private investors.

To learn more about how we apply these and other innovations, please feel free to get in touch now!

Contact

Maurits van Joolingen

Managing Director, Climate Scenarios & Sustainability